Spencer Merolla

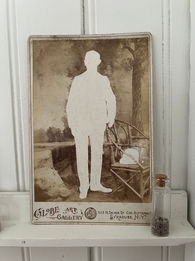

The Unfixed series emerged during a residency at the Bard Graduate Center Library. I had been investigating early photography, which was tremendously popular because it promised its sitters an affordable means to ensure they wouldn’t be forgotten. In 1859, Oliver Wendell Holmes dubbed the daguerreotype “the mirror with a memory.” Forty years later, speaking of the Brownie camera, Kodak’s George Eastman declared that it "enables the fortunate possessor to go back by the light of his own fireside to scenes which would otherwise fade from memory and be lost.”

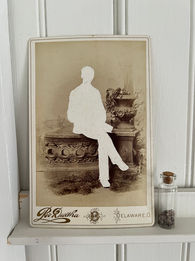

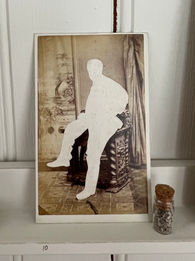

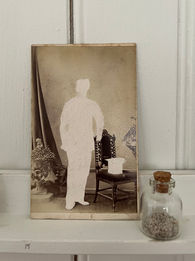

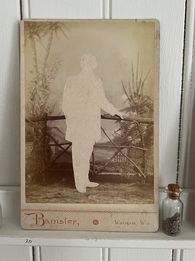

Photographs, also known as “sun pictures," had an advantage over portrait painting beyond their affordability: each one was a direct capture of the real, unmediated by a painter’s interpretation. This is their indexical quality; like a death mask or a shadow, they have a physical connection to what they depict, and a kind of truth which results from the mechanics of the photographic process. The sun that bounced off the face of each sitter passed through a lens to darken a plate of glass, which in turn coaxed an image in the silver in the paper. It’s this that I scrape off into a jar.

When is a person forgotten? When their identity is disconnected from the photograph? If a loved one isn’t around to remember, when do those whose likenesses were captured cease to be? If the photograph is an index, then its fragmentation is a manipulation of something more direct than a mere symbol. It is dust, but not just any dust: rather, it is a physical trace of light on the subject's face rendered unreadable, but not–as yet–lost. It hovers between dissolution and dispersion, just this side of oblivion.

click for full image & details